After I wrote this dispatch I read “Your Phone Was Made By Slaves” by Kevin Bales and immediately felt silly — his longer piece covers a lot of the same ground in more depth. If you find this topic interesting, it’s a good read.

Computers, cell phones, and other electronic devices contain conflict minerals. For those of you unfamiliar with the term: “Conflict resources are natural resources whose systematic exploitation and trade in a context of conflict [AKA a war zone] contribute to, benefit from or result in the commission of serious violations of human rights”. Furthermore, “Take away the ability to profit from resource extraction and [the fighting groups] can no longer exacerbate or sustain conflict.”

To provide an example, minerals in the Democratic Republic of the Congo are mined by rebel militias and sold to fund the continuation of the fighting. The buyers are nobody in particular, but those minerals are laundered the way illicit money is laundered, by being passed through middlemen. Eventually manufacturers use the minerals on behalf of multinational purveyors of consumer electronics. Big companies — brand names that you would recognize. And so the violence continues, because local warlords want to keep access to their money machine. (If you have a Netflix account, I recommend watching the investigative documentary Virunga to learn more about this.) The DRC is only one of the places devastated by neocolonialism paired with local power-mongering.

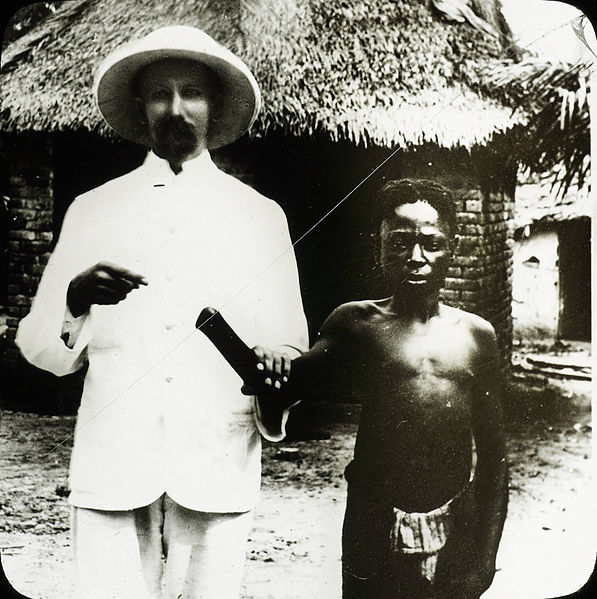

Image via Wikimedia Commons.

The photo above dates from the late 1800s or early 1900s. According to USC’s caption, “The Congolese man is likely to have been a victim of the ‘Congo atrocities’, punishment, murders and mutilations (particularly amputation of the right hand on living victims or after death) that took place on colonial rubber plantations in the Congo Free State, territory owned by Belgian King Leopold II […] Workers on rubber plantations were paid with worthless goods, and it was in noticing this imbalance of trade that shipping clerk Edmund Morel reported in his columns for The West African Mail, noticing that large numbers of weapons were going into the country to control the rubber workers.” I call it neocolonialism because we are continuing an old pattern, just shuffling the guns around.

The New York Times’ East Africa bureau chief Jeffrey Gettleman wrote in a piece for National Geographic:

“In the ensuing free-for-all [after dictator Mobutu Sese Seko was deposed and Congo was consumed by war], foreign troops and rebel groups seized hundreds of mines. It was like giving an ATM card to a drugged-out kid with a gun. The rebels funded their brutality with diamonds, gold, tin, and tantalum, a hard, gray, corrosion-resistant element used to make electronics. Eastern Congo produces 20 to 50 percent of the world’s tantalum.”

How do we cope with this, as consumers? Do we drop out of modern life, eschewing all the connected devices that have become standard in the “First World”? Do we cling to guilt and shame because we don’t care enough to actually change our behavior? I’ll admit it: I don’t care enough about this problem to sacrifice my iPhone or my laptop. I’m not going to switch to a Fairphone. Neither do I only buy fair-trade food and clothing.

So, should I blame myself for the war in the Democratic Republic of the Congo? Is it my fault and yours? I’m genuinely undecided. On one hand, the demand side of a transaction doesn’t specify the methods of the supply side. I didn’t ask anyone to buy from militias. I didn’t ask the seventeenth-century European superpowers to pursue mercantilism and shoulder the spurious “white man’s burden”. On the other hand, I am funding terrorism, albeit very indirectly. Amnesty International released a report on cobalt sourcing in January — it’s pretty clear that this is not a resolved issue.