Tyler Callich (also known as @lichlike) is a storyteller who makes Twitter bots, among other narrative vehicles. “Lich” is the last syllable of her last name, and it’s also a type of creature that exists between life and death. Wikipedia edifies us:

“Unlike zombies, which are often depicted as mindless, part of a hivemind or under the control of another, a lich retains revenant-like independent thought and is usually at least as intelligent as it was prior to its transformation. In some works of fiction, liches can be distinguished from other undead by their phylactery, an item of the lich’s choosing into which they imbue their soul, giving them immortality until the phylactery is destroyed.”

Tyler’s symbol — her conceptual avatar, if you will — is the lich. When I spoke to her on the phone, she reflected, “I like the concept of this liminal half-dead, half-alive, potent-but-still-waning [being].” A lich is “like a ghost, but not quite” — essence externalized. “It’s one way I conceive of identity, also. It’s in this removed far-outside-of-me place, like a phylactery.” Somewhat akin to @lichphylactery, which shakes up Tyler’s words and spills them back in new arrangements.

That particular creation is Tyler’s own phylactery, a Markov-based ebooks bot with a straightforward name. It says things like, “One and all bring its water which they observe are the 3 styles we’re featuring?” Another recent comment: “Atlnaba a All comprehended within the form of these systems upon the doctrines of the informers were led off s訖”

Tyler explained, “With Markov chains, you’re taking some text and using its grammar to make something new, but still sensible or almost sensible.” She noted that “unintelligible nonsense is novel for a little while”, but it gets boring. Bots like @lichphylactery — or Olivia Taters — are best when they’re close to passing the Turing test, but still not quite there.

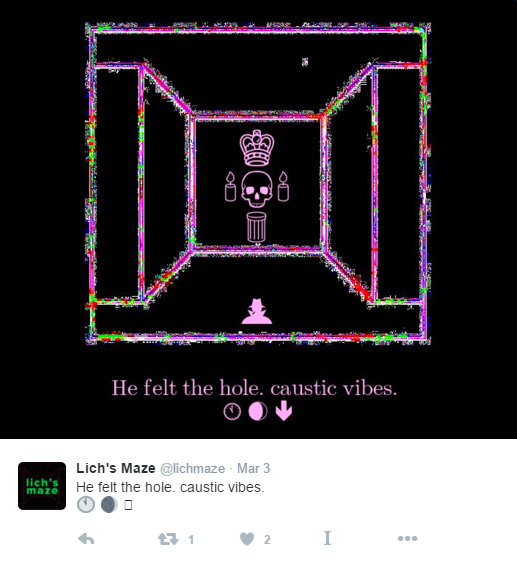

My favorite of Tyler’s projects is Lich’s Maze. Here is a recent @lichmaze micro-story:

The bones of Lich’s Maze are a loose mythological system that Tyler put together. She fed it a corpus of text, some that she wrote and some that she found. Then she released @lichmaze to wander through people’s Twitter feeds, sending out cryptic moments from an arcane techno-magic game-world.

Tyler told me, “Symbolic thinking is a way for me to just let my mind wander through association.” She “can get a computer to make random associations for me” which “augments that free-thinking / brainstorming”. I asked if she uses @lichmaze’s output as writing prompts, and surprisingly the answer was no. Tyler answered in a thoughtful voice, “It never really occurred to me.”

Beau Gunderson said of Twitter bots, “they’re creators but i don’t put them on the same level as human creators. […] i’m giving the computer the ability to express a parameter set that i’ve laid out for it that includes a ton of randomness.” On the other hand, Tyler doesn’t feel a strong ownership claim. “I take a big backseat to that.” She said, “I think of [the bot] as its own entity after a certain point. It’s kind of independent from me.” She even wishes “that it could change the password on itself and go off on its own”, in a direction unspecified. Tyler’s bots are probably best compared to a growing tangle of plants. Tyler told me, “I think randomness is natural [and] finding that grit or that little kink in digital art is something that I connect closely to organic structures.”

Another project of Tyler’s is Restroom Genderator, which comes up with “extant (and not so extant) genders”. This is a perfect example of “taking a concept and pushing it toward its eventual ruin”, as Tyler put it. A bot like Restroom Genderator is tireless and thorough — eventually “you get a rich contour of all of the iterations of something”. It was originally based on a joke with a friend. “The initial concept — you come up with something and you’re like, ‘Oh, this is funny!’ It can become kind of mundane after a while to write out five thousand combinations and figure out what the best one would be.” So you construct a bot to do it for you.

Asked to define her practice, Tyler told me, “I would consider myself a writer, but it’s hard because I don’t write, like, novels usually.” She continued, “If I was working in a normal platform, I would consider myself a poet, but that seems kind of lofty. I consider myself a tinkerer more than anything else… like a word tinkerer.”