One of the most interested things that happened this week was an AWS outage. For those of you who aren’t familiar, Amazon Web Services is a sophisticated cloud host for websites and apps. It is very widely used, especially among startups. When it goes down, as it did on Tuesday, many tech workers can’t do their jobs. At least Twitter was still available, providing a convenient location for complaints. (Additional discussion took place on Hacker News.)

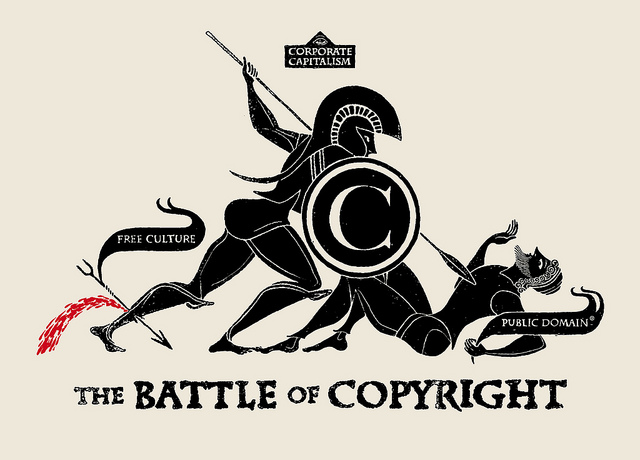

I wrote about the incident for work, first summing up reactions from Twitter and then making the case that AWS is not a monopoly and shouldn’t be regulated as such. In response to that argument, my friend Adam Elkus pointed out that decentralized infrastructure was a founding ideal of the internet. The beautiful new world of http://www was supposed to empower individuals at the expense of institutions, be they governmental or private.

It has done that — but as usual, the reality is more of a complex onion than the idealists seemed to expect. In my first Ribbonfarm essay, I wrote:

The internet enables more individual opportunity than ever before — how would my words manage to reach you otherwise? And the internet is more meritocratic than the landscape it took over, because anyone can distribute their own work to a potential audience of millions, but of course age-old power dynamics can’t be erased in one fell swoop. It also enables winner-take-all businesses, like Amazon’s dominance in ecommerce and Facebook’s reign over news media.

Centralization wins because it’s efficient, given the constraints and affordances of the internet. And yet this centralization can be penetrated — not dismantled, but surface segments can be peeled back. That’s what hackers do when they leak a database or whatever.

One of cyberpunk’s central insights, as an ethos, was that the internet gives individuals more power at the same time that amoral, corporatized institutions build up their strongholds. It’s funny that some of the same people — the cypherpunks, say — explicitly bridged cynical cyberpunk and sunny techno-utopianism.

In John Perry Barlow’s “Independence of Cyberspace” manifesto, presented to “Governments of the Industrial World” at Davos, he said:

The global conveyance of thought no longer requires your factories to accomplish. […] We must declare our virtual selves immune to your sovereignty, even as we continue to consent to your rule over our bodies. We will spread ourselves across the Planet so that no one can arrest our thoughts.

No one can arrest our thoughts, unless they’re hosted on AWS — a factory of the information economy if there ever was one — in which case someone fat-fingering a command kicks your thoughts into the inaccessible nowhere of a disconnected server farm. It’s impossible not to be at someone’s mercy.

Header artwork by Igor Kirdeika.

![Photo by Newtown grafitti [sic].](../../wp-content/uploads/2016/09/6399125415_d078297594_b.jpg)