“Always have 3D glasses — you never know what you might run into.”

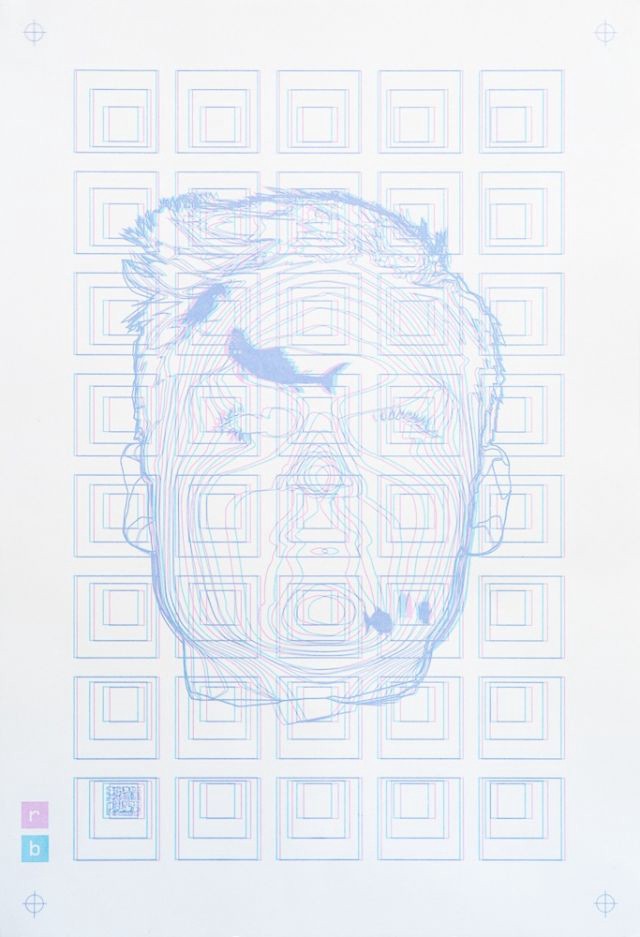

I talked on the phone with Charles Robertson of Sediment Press (remember cyberpunk Santa Claus?). He gave me that advice about 3D glasses. The above self-portrait, CR Anaglyph, is best viewed with such eyewear. I told him that I thought my readership was more likely to have 3D glasses than the average Joe, but I couldn’t guarantee anything.

Charles made the topographical map of his face using analogue methods — he lay on his back in a bathtub and had a friend take photographs while the waterline progressively rose. Looking at the snapshots later, he traced the waterline at different levels and compiled the tracings into one composite image.

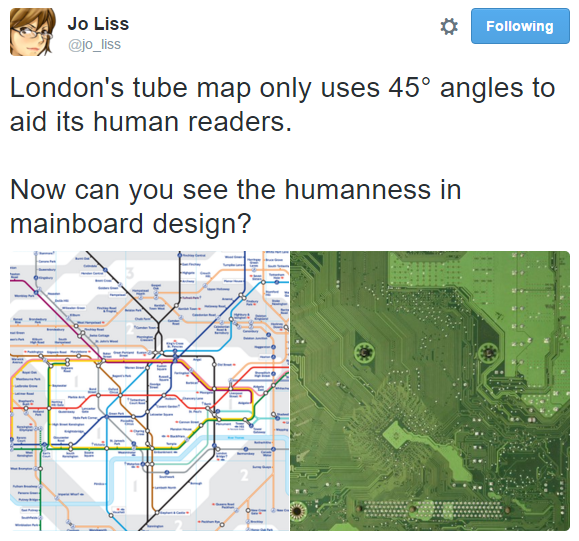

We discussed maps, a recurring theme in Charles’ work. “You can represent a lot of information in a small space. […] A piece of eight-and-a-half-by-eleven paper can be an entire city.” He likes the aesthetic effect, too: “You set out to do something practical, but out of that you get these shapes, and colors, and geometries.” We talked about the homologies that arise from human design — have you ever noticed that a subway map looks like a computer chip?

Charles and his creative partner Tim Lovelace have been working on Sediment Press since 2011. They met at a screen-printing class. Now they live in different cities — Tim maintains a small studio in his home, and Charles does a lot of the design work, although each of them practices both parts of their craft. Sediment Press is fundamentally a collaboration.

We use maps to keep track of ourselves, where we’re situated. They are abstractions, never able to match the detail or roughness of real terrain. Yet maps also function as grounding devices. “I am here. These are the contours of my face. The context is clear.” Most maps are frozen in time — they represent a slice of eternity. If he had waited a week, the waterlines on Charles’ face would be different. Only a little, I’m sure, but different.