It’s been ages since I sent you fiction. This half-story has been kicking around in my Google Drive for months, and even though it doesn’t have a normal plot or resolution, I hope it will interest you. Suggestions of what might happen next are welcome. Either way, think of this dispatch as a foray into a world based on Exolymphian principles.

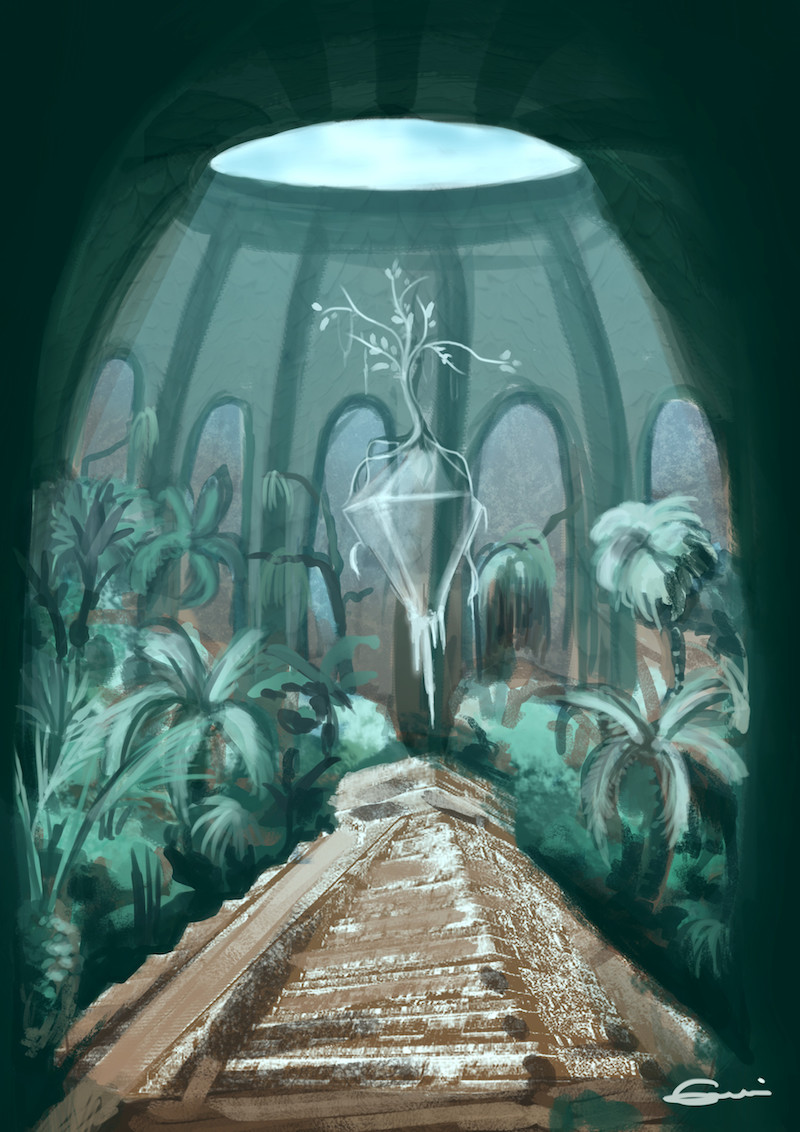

Artwork by Ricardo Orellana.

“It is a strange wind that blows no ills.” This is what Attwell’s grandmother told him, in her warm, wry voice. They stood in front of a clear window, high up in the arcology. Attwell could see her scalp through the silver hair on her head. Earlier she had mentioned that a cousin offered to buy her a full-body resurfacing, but she planned to decline. “Why bother?” Nana had chuckled.

Now, glancing down at her, Attwell felt slightly embarrassed by the visible skin of her scalp. He ought to look away.

The wind that blew against the window was thick with dust. All they could see was the movement of the air. “It is a strange wind that blows no ills,” Nana repeated.

This conversation took place before she died, as all people must die. Before she was recycled, as all empty bodies must be. Attwell knew that her substances would nourish the arcology. Her generation was dropping one by one, two by three by four by five, and their deaths helped to sustain their children. Chickens and pigs had no sentimental qualms about an old woman’s flesh.

Attwell wished that personality-preservation had existed before the cancer ate up Nana’s brain. Even the stilted simulation of a first-generation model would be a comfort to him now. But perhaps she would have been content to disappear completely.

It was twelve years ago that Nana died. A few days after her body had been surrendered, the computer that coordinated the arcology offered usage stats to Attwell. This percentage went to mineral reclamation, that percentage went to agriculture, and so on. The computer instructed, “Please engage the Cycle of Life grief-management module. This is a complimentary offer, available until” — then Attwell blanked the screen with a harsh motion. He sat on the carpet and wept.

Even now, more than a decade later, Attwell longed to speak to Nana again. If her essence were available as a Dearly Departed® program, Attwell could upload pictures of his new suite, to show her his success. He could demonstrate the screen-morphs that disrupted the monotony of the arcology. Attwell felt sure that Nana would want to explore the reconstructed immersion vistas of rainforests and sunny beaches. And he would tell her about the scientists preparing for expeditions to reclaim the outside world, microbiome by microbiome. The news-beams warned that a manned mission was still decades away, but Attwell hoped it would happen sooner than that.

Attwell was estranged from the rest of his family. Grief had turned to bitterness after Grandpapa’s death, and every segment of the clan came to suspect the others of villainous perfidy. Inheritances are a hard thing. Six of them came to live in the arcology when it was established, but they still never spoke to each other. One cousin’s suite was on Attwell’s level, but the pair had affected indifference so well that it came true. Attwell felt as if he had never known this cousin at all.

Their respective parents had both refused to enter the arcology, calling it a project of Satan. Attwell suspected that they had perished in the howling dust storms many years ago. Nana was always more sensible than her children.

Attwell was not alone, and he didn’t spend all of his time pining for a lost grandmother. Not long after the twelfth anniversary of Nana’s death, incidentally, he held a dinner party for his friends. Two of them were lapsed members of the Sunsplit doomsday cult. (It had lost steam after the predicted doomsday actually came to pass. The arcology chugged along just fine. Mourning rites were still held quarterly, and a fanatic core remained, but general attendance kept slipping.)

At the table these two quarreled about a fine point of the law written by the Sunsplit founder, part of a document officially titled `revealed_arcana4j.txt`. Most people referred to it as the Revealed Arcana, for convenience. Sunsplit lore reported that the First Priest sat down to write a SCRUM report for his manager, found his fingers hijacked by a higher power, and spent seventy-four hours typing sacred secrets. Skeptics often attributed this episode to a layered cocktail of amphetamines and hallucinogens. They couldn’t dismiss the incident altogether, since the First Priest’s computer had been forensically examined.

Atwell’s friends were arguing about the prohibition against killing and consuming phoenixes. The mythical phoenix is a large bird with red and gold plumage, which never dies unless intentionally slain. When it perishes from old age, there is a burst of flame. A phoenix chick emerges from the ashes of its previous life cycle after the blaze subsides.

The rest of the party looked on, bemused, as the Sunsplit believers went back and forth.

“Why forbid the eating of a phoenix,” Timothy asked, “if there is no such an animal in nature?”

A noncombatant chimed in, “Maybe there used to be, before the dust” — but was quickly shushed.

“There must necessarily be such an animal!” replied Valeria, “There’s no sensible reason for the rule to exist, otherwise, and of course the First Priest was sensible.”

Attwell pointed out, “If there are no phoenixes, we cannot possibly slaughter them. Either way, all of us are following the Sunsplit doctrine, without even trying.”

The guest who attended by hologram said, “Did you know that the nanotech fellows at Companion Labs aren’t even trying to make a phoenix, because it would be such bad press?”

“What about an effigy?” Attwell asked. “What if I 3D-printed a phoenix out of cake and ate it?”

Valeria snorted, half amused and half contemptuous. Timothy opened his mouth but someone else cut in before he could speak.

“Haven’t any of you played the phoenix game?” This was the first time Lydia had spoken since the appetizers.

“No, what’s that?” the hologram guest inquired.

Lydia shrugged her thin shoulders. Atwell thought she seemed uncomfortable with the table’s full attention. “Just something I heard about. You harvest phoenixes.”

“I don’t know if it breaks the First Priest’s law,” Valeria declared, “but it’s certainly obscene.”

Not wanting Lydia to be steamrolled, Atwell hurried the conversation in another direction. But after the guests straggled out of his suite that night, he sent her a message.

> what’s the name of that game you mentioned? i searched and nothing came up

She responded almost instantly.

> i shouldnt have said anything =/

> why not? it sounded interesting. i like obscure games. You know how i am

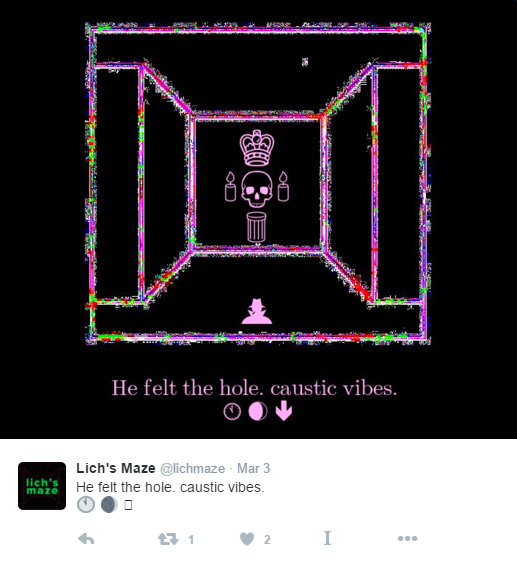

Lydia didn’t respond, but a few minutes later, he received a message from the username vezik77. It was just a hyperlink. No preview popped up. Was this just spam, or did it have something to do with the conversation? Attwell copied the link, opened a sandbox browser, and pasted it into the address bar.

That’s it!

Very loosely inspired by “The Envious Man” from Voltaire’s Zadig the Babylonian, via Project Gutenberg.