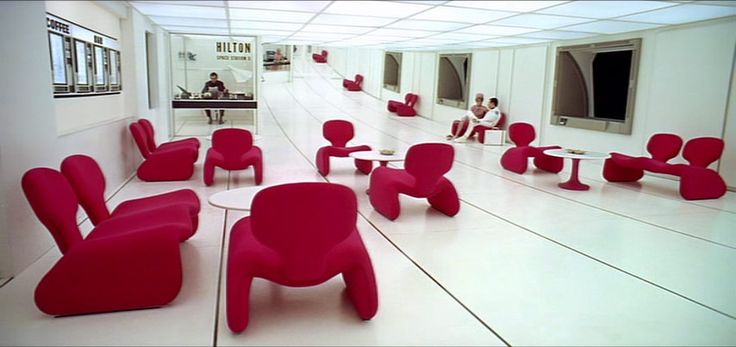

What does futuristic furniture look like? It depends on when you’re asking. The aesthetic we imagine for the future shifts depending on the decade defining it. For instance, the interior of the space shuttle in 2001: A Space Odyssey looks quaint in retrospect, but felt cutting-edge at the time.

Sleek white floors and ceilings, offset by scarlet Koonsian chairs, in 2001: A Space Odyssey.

And yet we’ve held onto some of the trends that preoccupied the design futurists of the late 1960s — stark colors (or absence thereof), shiny opaque surfaces, and an ineffable sense of mystery are all still crucial. In fact, we haven’t moved very far from modernist forms; the computer screens were updated, but not their surroundings. In general, the surfaces are simple, and the shapes are either rounded or defined by plain rectangular angles.

Observe this set of ascetic end tables built by Patrick Cain Designs, which are explicit evocations of modernist style, and which wouldn’t feel out of place in a venture capitalist’s office:

Two powder-coated white end tables by Patrick Cain Designs.

Or this much more intricate end table that plays with interlocking patterns while restricting itself to right angles:

Black-painted steel end table with a glass top, sold by Etsy shop ObjectOfBeauty.

The vendor writes of the latter table:

“The overall style is very reminiscent of Paul Evan’s metal furniture creations as well as Harry Bertoia’s metal sculptures. The design includes a brutalist style decorative detail also representative of the period and the aesthetics of the aforementioned artists — three gold tone, textured discs (appear to be gold leaf plated).”

And yet this clean, intellectual vision of the future is artificially limited, only addressing the conditions of a digitized technocracy, and even then only depicting the upper classes. Another vision of futuristic furniture and next-century decor significantly differs from this pattern. The post-apocalyptic movie Snowpiercer imagines a stratified aesthetic stack — gritty, Dickensian slum conditions for the proles versus baroque, almost steampunk lushness for the rich.

Where the poor people live in the dystopian movie Snowpiercer — a different take on futuristic furniture.

The desk of the teacher who raises well-off children in Snowpiercer.

The bourgeois tea-party paradise in Snowpiercer.

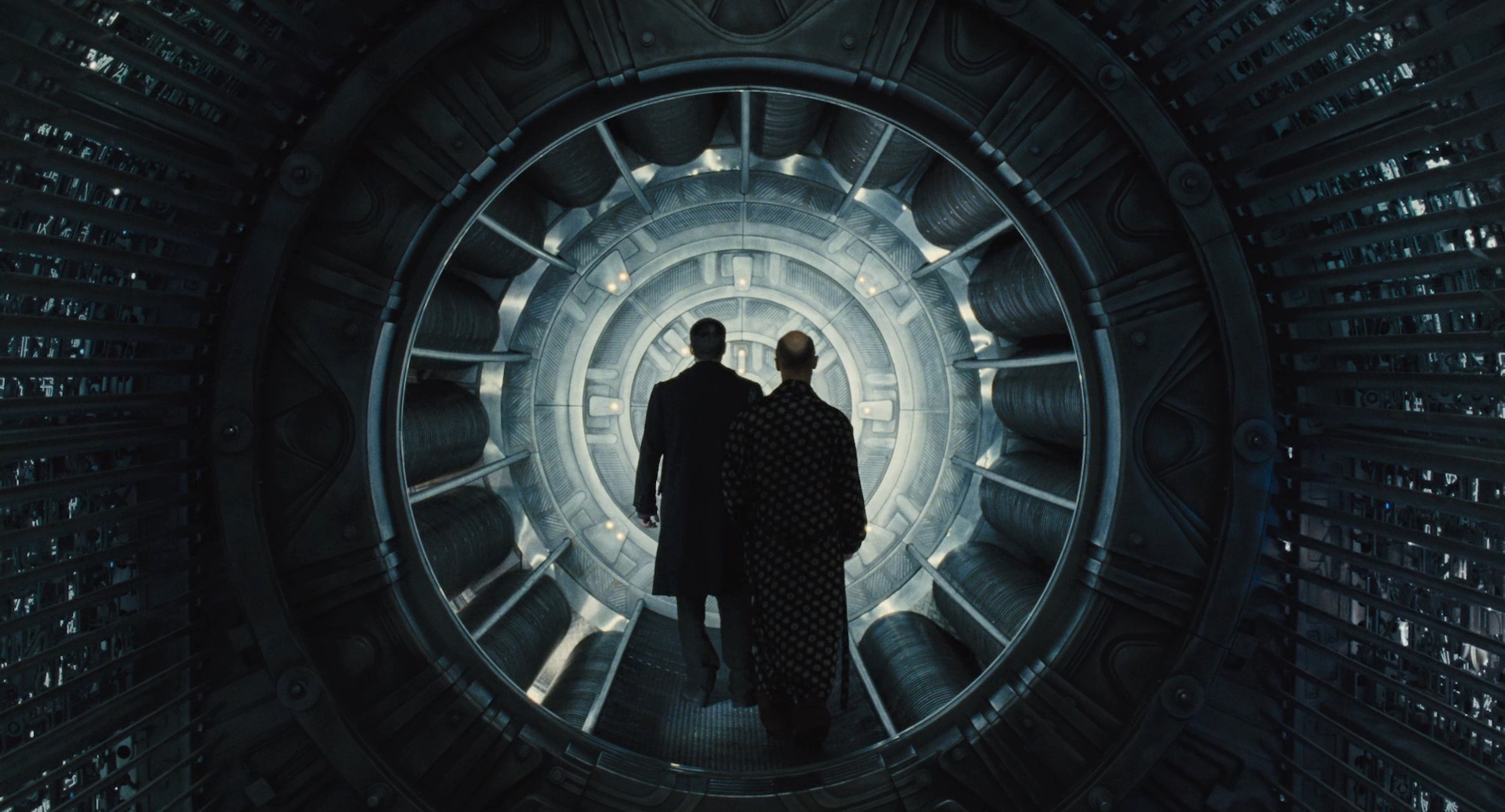

However, Snowpiercer‘s depiction of ultimate power recalls the tunnels and sleekness of 2001: A Space Odyssey, albeit with more embellishments:

The control center in Snowpiercer.

Perhaps futuristic-ness — futuristicality? — doesn’t so much depend on visual specifics as it does on the political and technological context. Which has been my thesis about cyberpunk all along…