Today’s dispatch was contributed by Ken Rodriguez.

I recently watched the first installment of The X-Files’ new six-part series. In order to avoid spoilers, let’s say that the conclusion is surprising and expected at the same time. The government is hiding more — and less — from us than we think (according to the show’s plot). Watching it reminded me of a thought that I had several months ago (when no one was encouraging me to write about it). I was wondering whether “the powers that be” allow us to have a certain amount of entertainment that criticizes government and corporate intervention in our private lives. Are movies and shows like The Machine, Breaking Bad, and Idiocracy rationed at a high enough frequency to let us blow off some steam, but not so often that we can keep the concepts in our collective minds and put the pieces together? Is there more than an element of truth in what these shows contain?

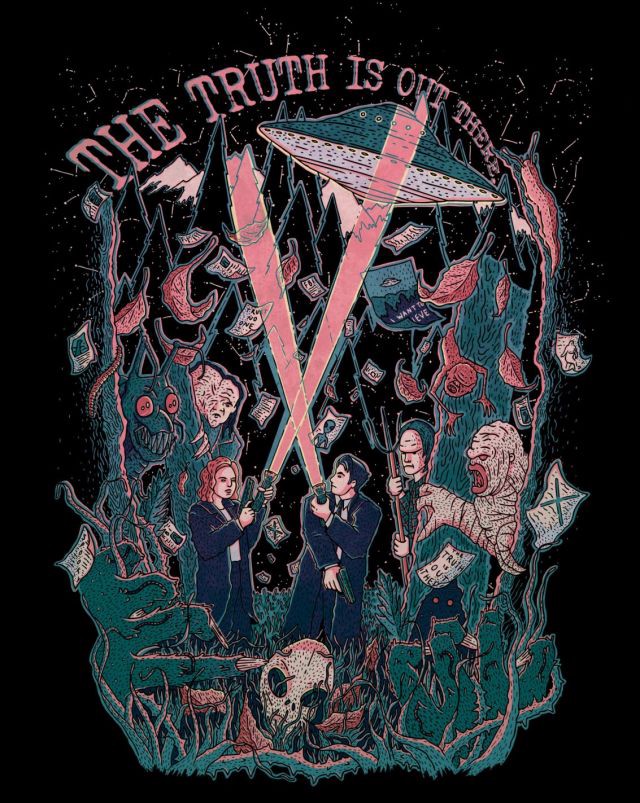

Scully and Mulder depicted by Taylor Rose; $30 on Etsy.

The American public is maddeningly forgetful and inattentive. We see it in our lionization of figures such as Oliver North, George Gordon Liddy, and Howard Dean. Even Patty Hearst and OJ Simpson have a certain cachet. We scare ourselves with movies like The Matrix and Terminator, happy to idly ponder if we’re really being controlled by something outside of ourselves — but then we go home, crack open a beer, watch the game, and go to bed. We go on with our lives because, really, what are we going to do about it? We need food. We need shelter. We have children. People are depending on us. It’s easier and safer to go on as we have because to do otherwise is to face the possibility of disgrace, upheaval, or worse.

Since 1999, Donald Trump has quit the Republican party, been a Reform Party candidate, a Democrat, and a Republican. Does anyone remember this? We’re too busy being entertained by him to consider his policies. Barack Obama came into office on a left-wing wave against government conservatism, only to deport more immigrants than any other president before him and mount a drone war that makes him look as hawkish as George Bush. We didn’t protest when Obama failed to employ grand juries to investigate the banks and brokerages behind what we are calling the “Great Recession”. If it isn’t in our faces right now, it never existed.

This ignorance exists in an era when there is more information available than ever before, and it is right at our fingertips. Yet we know more about our Netflix queue and our Facebook friends than we do about who is the vice president. Anybody remember Google Glass? The evening news only carries the most sensational stories because ratings are more important than current events. Are we amusing ourselves to death?

Contemporary entertainment is full of conspiracy theories and government plots to exert more control over the citizens. Corporations are demonized regularly. These works reflect the reality that we see in targeted advertising, the Patriot Act, and the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, to name just a few. When we go to the movies or watch our favorite shows, we rail against the intrusive government or the evil corporations. We feel angry about what is being done to us by the faceless entities that we fear.

Chris Carter, before the first run of The X-Files, was afraid the FBI was about to “shut [him] down”. We may even think ourselves smarter than the average American zombie because we see through the commercial propaganda that permeates even the programming we pay for (remember when cable TV had no commercials?). But when someone tries publicly to do something about these intrusions, they are “too radical” or a “weirdo socialist”. We like to see someone in the movies succeed against the oppressors, but we don’t want to be the one who sticks their neck out. We’ve heard too many stories like those of John Savage in Brave New World or Winston Smith in 1984.

With all of these anti-authoritarian ideas out there, how much is enough to make us break out the pitchforks? Or is it this very content that prevents rebellion? The cyberpunk Facebook page where I hang out has plenty of curmudgeons and anarchists. There’s copious ranting about government intervention in our private lives and about corporate control of media and government. Weekly we have a dustup about some meme or post that the administrators deleted. Are we defeating our own angst by having these blowoffs?

We experience the effects of endorphins when our brains shift from left to right during TV watching. This is what gets us addicted to visual media. Is this pleasure short-circuiting our outrage, making us docile and suggestible? Or have we just not yet reached a critical mass in our frustration? Or are we afraid that, like Howard Beale in Network, if we’re “mad as hell” and are “not going to take it any more”, we will end up like him, with the corporate media having appropriated even our anger and rebellion?